Trump DOJ asks Supreme Court to freeze student debt, environment cases

The Trump administration asked the Supreme Court to freeze several pending cases on student loans and the environment

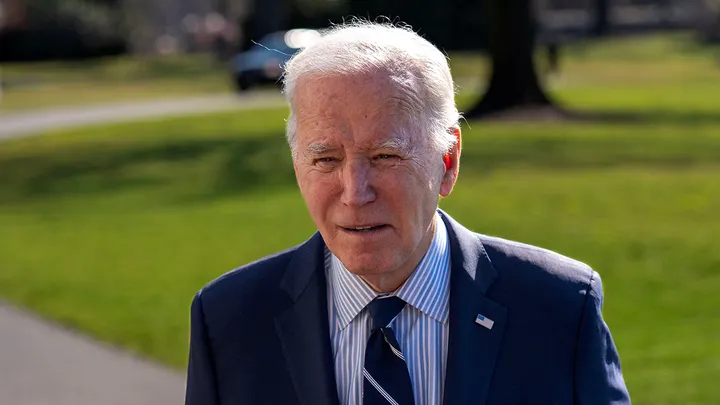

President Donald Trump’s Justice Department on Friday asked the Supreme Court to freeze a handful of cases, including a challenge to one of former President Biden’s student loan bailouts.

Acting Solicitor General Sarah Harris filed several motions Friday asking the court to halt proceedings in the student loan case and three environmental cases while the new administration will “reassess the basis for and soundness” of Biden’s policies.

The Supreme Court was expected to hear oral arguments for these cases in March or April and issue decisions later this term. But Trump’s DOJ requested that the high court halt all written brief deadlines, which would put them on indefinite hold.

Under former President Joe Biden, more than 5 million Americans had their student debt canceled through actions taken by the Department of Education. But Biden’s actions faced numerous legal challenges, with GOP critics alleging he went beyond the scope of his authority by acting without Congress.

In this case, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals had blocked the Biden administration’s borrower defense rule, which would have expanded student debt relief for borrowers who were defrauded by their schools. The court found that Biden’s rule had “numerous statutory and regulatory shortcomings.” Biden appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case earlier this month.

Now, that case is on hold, and it is possible the Trump administration will revoke the rule change, rendering the issue moot.

The three environmental cases have to do with regulations issued by the Environmental Protection Agency during the Biden administration that were challenged.

It is not unusual for a new presidential administration to reverse its position on legal cases inherited from the prior administration. After Biden took office, the DOJ asked the Supreme Court to freeze a challenge to Trump’s attempt to use military funds to construct a border wall. Biden halted the spending and the court dismissed the case.

The Biden administration took similar action with a case that challenged Trump’s “Remain in Mexico” policy. The Supreme Court eventually tossed the case as moot after Biden rescinded the policy.